The Battle of Messines (7–14 June 1917) was an attack by the British Second Army (General Sir Herbert Plumer), on the Western Front, near the village of Messines (Dutch: Mesen) in West Flanders, Belgium, during the First World War. The Nivelle Offensive in April and May had failed to achieve its more grandiose aims, had led to the demoralisation of French troops and confounded the Anglo-French strategy for 1917. The attack forced the Germans to move reserves to Flanders from the Arras and Aisne fronts, relieving pressure on the French.

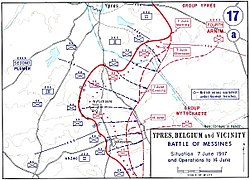

The British tactical objective was to capture the German defences on the ridge, which ran from Ploegsteert Wood (Plugstreet to the British) in the south, through Messines and Wytschaete to Mt Sorrel, depriving the German 4th Army of the high ground. The ridge gave commanding views of the British defences and back areas of Ypres to the north, from which the British intended to conduct the Northern Operation, an advance to Passchendaele Ridge and then the capture of the Belgian coast up to the Dutch frontier. The Second Army had five corps, three for the attack and two on the northern flank not part of the operation; XIV Corps was in General Headquarters reserve. The 4th Army divisions of Group Wytschaete (Gruppe Wijtschate, the IX Reserve Corps headquarters) held the ridge and were later reinforced by a division from Group Ypres (Gruppe Ypern).

The British attacked with the II Anzac Corps (3rd Australian Division, New Zealand Division and the 25th Division, with the 4th Australian Division in reserve), IX Corps (36th (Ulster), 16th (Irish) and 19th (Western) divisions and the 11th (Northern) Division in reserve) and X Corps (41st, 47th (1/2nd London) and 23rd Divisions with the 24th Division in reserve). XIV Corps was in reserve, with the Guards Division, 1st Division, 8th Division and the 32nd Division. The 30th, 55th (West Lancashire), 39th and 38th (Welsh) divisions, in II Corps and VIII Corps, guarded the northern flank and made probing attacks on 8 June. Gruppe Wijtschate held the ridge with the 204th, 35th, 2nd, 3rd Bavarian (relieving the 40th Division when the British attack began) and 4th Bavarian divisions, with the 7th Division and 1st Guard Reserve Division as Eingreif (counter-attack) divisions. The 24th Saxon Division, relieved on 5 June, was rushed back when the attack began and the 11th Division, in Gruppe Ypern reserve, arrived on 8 June.

The battle began with the detonation of nineteen mines beneath the German front position, which devastated it and left large craters. A creeping barrage, 700 yd (640 m) deep, began and protected the British troops as they secured the ridge with support from tanks, cavalry patrols and aircraft. The effect of the British mines, barrages and bombardments was improved by advances in artillery survey, flash spotting and centralised control of artillery from the Second Army headquarters. British attacks from 8 to 14 June advanced the front line beyond the former German Sehnenstellung (Chord Position, the Oosttaverne Line to the British). The battle was a prelude to the much larger Third Battle of Ypres, the preliminary bombardment for which began on 11 July 1917.