Paul's walk in Elizabethan and early Stuart London was the name given to the central nave of Old St Paul's Cathedral, where people walked up and down in search of the latest news. At the time, St. Paul's was the centre of the London grapevine. "News-mongers", as they were called, gathered there to pass on the latest news and gossip, at a time before the first newspapers. Those who visited the cathedral to keep up with the news were known as "Paul's-walkers".

According to Francis Osborne (1593–1659):

It was the fashion of those times, and did so continue till these . . . for the principal gentry, lords, courtiers, and men of all professions not merely mechanic, to meet in Paul's Church by eleven and walk in the middle aisle till twelve, and after dinner from three to six, during which times some discoursed on business, others of news. Now in regard of the universal there happened little that did not first or last arrive here...And those news-mongers, as they called them, did not only take the boldness to weigh the public but most intrinsic actions of the state, which some courtier or other did betray to this society. Amongst whom divers being very rich had great sums owing them by such as stood next the throne, who by this means were rendered in a manner their pensioners. So as I have found little reason to question the truth of which I heard then, but much to confirm me in it.

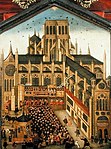

Standing on Ludgate Hill in the heart of the City of London, St Paul's Cathedral was well placed to be a hub of news. The cathedral had once been among the greatest in Europe, but a decline set in after the Reformation and by the end of the sixteenth-century, it had lost its steeple and was falling into disrepair. The cathedral and its surrounding St. Paul's Churchyard was a centre of the booksellers' trade, a venue for sellers of pamphlets, proclamations, and books. St Paul's was the place to go to hear the latest news of current affairs, war, religion, parliament and the court. In his play Englishmen for my Money, William Haughton (d. 1605) described Paul's walk as a kind of "open house" filled with a "great store of company that do nothing but go up and down, and go up and down, and make a grumbling together". Infested with beggars and thieves, Paul's walk was also a place to pick up gossip, topical jokes, and even prostitutes. John Earle (1601–1665), in his Microcosmographie (1628), called Paul's walk "the land's epitome . . . the lesser isle of Great Britain . . . the whole world's map . . . nothing liker Babel".Official attempts to stem the use of St. Paul's for non-religious purposes repeatedly failed. Both Mary I and Elizabeth I issued proclamations against "any of her Majesty's subjects who shall walk up and down, or spend the time in the same, in making any bargain or other profane cause, and make any kind of disturbance . . . during divine service . . . [on] pain of imprisonment and fine". Scholar Helen Ostovich has called St. Paul's at this time "more like a shopping mall than a cathedral".

The letter writer John Chamberlain (1553–1626) walked to St. Paul's each day to gather news on behalf of his correspondents. His main purpose in his letters was to relate news of events in the capital to his friends, especially those posted on the continent, such as Ralph Winwood and Dudley Carleton, who both spent much of their political careers at the Hague. Chamberlain proved the perfect source for Carleton and others because of his willingness to "walk Paul's" for the news. He was made a member of a commission to refurbish St. Paul's but was cynical about its chances. He wrote that the king was "very earnest to set it forward, and they begin hotly enough" but feared it would prove "as they say, Paul's work".King James was aware of Paul's walk and referred to it in his poem about a comet, seen in 1618, which was talked of as signalling doom for the monarchy: "And that he may have nothing elce to feare/Let him walke Pauls, and meet the Devills there". Chamberlain reported that the comet "is now the only subject almost of our discourse, and not so much as little children but as they go to school talk in the streets that it foreshows the death of a king or queen or some great war towards".Ben Jonson (1572–1637) set a pivotal scene of his play Every Man Out of His Humour (1599) in Paul's walk. As Cavalier Shift enters and begins posting up advertisements, Cordatus introduces the scene with the words: "O, marry, this is one for whose better illustration we must desire you to presuppose the stage the middle aisle in Paul's, and that [pointing to the door on which Shift is posting his bills] the west end of it". The west end of the aisle was where advertisements, known as siquisses, were posted; those interested wrote a suggested meeting time and place at the bottom.According to Ostovich, Jonson conceived the Paul's-walking scene of the play as a "satirical nutshell" of London itself, presenting the walking up and down as "an obsessively competitive dance". This view of Paul's walk as a microcosm had already seen print in the cony-catching pamphlets of Robert Greene (1558–1592), who had depicted city rogues and tricksters preying on those who walked the aisles to gossip, smoke, and see the fashions. The playwright Thomas Dekker (1572–1632), in his "Paul's Steeple's Complaint" in The Dead Term (1608) and his Gull's Horn-book (1609), was another who wrote about Paul's walk. He recorded its use as a venue for fashion, saying of a gallant: "He that would therefore strive to fashion his legs to his silk stockings, and his proud gait to his broad garters, let him whiff down these observations; for, if he once get to walk by the book . . . Paul's may be proud of him".