Congress Poland, Congress Kingdom of Poland, or Russian Poland, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland, was a polity created in 1815 by the Congress of Vienna as a semi-autonomous Polish state and successor to Napoleon's Duchy of Warsaw. It was established in the ethnically Polish lands ceded by the French to the Russian Empire following Napoleon's defeat. In 1915, during World War I, it was replaced by the German-controlled nominal Regency Kingdom until Poland regained independence in 1918.

Following the partitions of Poland at the end of the 18th century, Poland ceased to exist as an independent state for 123 years. The territory, with its native population, was split between the Habsburg monarchy, the Kingdom of Prussia, and the Russian Empire. After 1804, an equivalent to Congress Poland within the Austrian Empire was the Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria, also commonly referred to as "Austrian Poland". The area incorporated into Prussia and subsequently the German Empire had little autonomy and was merely a province – the Province of Posen.

The Congress Kingdom of Poland was theoretically granted considerable political autonomy by the liberal constitution. However, its rulers, the Russian Emperors, generally disregarded any restrictions on their power. It was, therefore, little more than a puppet state in a personal union with the Russian Empire. The autonomy was severely curtailed following uprisings in 1830–31 and 1863, as the country became governed by viceroys, and later divided into governorates (provinces). Thus, from the start, Polish autonomy remained little more than fiction.The capital was located in Warsaw, which towards the beginning of the 20th century became the Russian Empire's third-largest city after St. Petersburg and Moscow. The moderately multicultural population of Congress Poland was estimated at 9,402,253 inhabitants in 1897. It was mostly composed of Poles, Polish Jews, ethnic Germans and a small Russian minority. The predominant religion was Roman Catholicism and the official language used within the state was Polish until the failed January Uprising when Russian became co-official as a consequence. Yiddish and German were widely spoken by their native speakers.

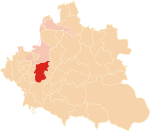

The territory of Congress Poland roughly corresponds to modern-day Kalisz Region and the Lublin, Łódź, Masovian, Podlaskie and Holy Cross Voivodeships of Poland as well as southwestern Lithuania and a small part of the Grodno District of Belarus.

The Kingdom of Poland effectively came to an end with the Great Retreat of Russian forces in 1915 and was succeeded by the Government General of Warsaw, established by the Germans. In 1917, part of this was renamed as the short-lived Kingdom of Poland, a client state of the Central Powers, which had a Regency Council instead of a king.