The newer Siloam Tunnel (Hebrew: נִקְבַּת הַשִּׁלֹחַ, Nikbat HaShiloaḥ), also known as Hezekiah's Tunnel (Hebrew: תעלת חזקיהו, Te'alát Ḥizkiyáhu), is a water tunnel that was carved within the City of David in ancient times, now located in the Arab neighborhood of Silwan in eastern Jerusalem. Its popular name is due to the most common hypothesis that it dates from the reign of Hezekiah of Judah (late 8th and early 7th century BC) and corresponds to the "conduit" mentioned in 2 Kings 20:20 in the Hebrew Bible. According to the Bible, King Hezekiah prepared Jerusalem for an impending siege by the Assyrians, by "blocking the source of the waters of the upper Gihon, and leading them straight down on the west to the City of David" (2 Chronicles 32:30). By diverting the waters of the Gihon, he prevented the enemy forces under Sennacherib from having access to water.

Support for the dating to Hezekiah's period is derived from the Biblical text that describes construction of a tunnel and to radiocarbon dates of organic matter contained in the original plastering. However, the dates were challenged in 2011 by new excavations that suggested an earlier origin in the late 9th or early 8th century BC.The tunnel leads from the Gihon Spring to the Pool of Siloam. If indeed built under Hezekiah, it dates to a time when Jerusalem was preparing for an impending siege by the Assyrians, led by Sennacherib. Since the Gihon Spring was already protected by a massive tower and was included in the city's defensive wall system, Jerusalem seems to have been supplied with enough water in case of siege even without this tunnel. According to Aharon Horovitz, director of the Megalim Institute, the tunnel can be interpreted as an additional aqueduct designed for keeping the entire outflow of the spring inside the walled area, which included the downstream Pool of Siloam, with the specific purpose of withholding water from any besieging forces. Both the spring itself, and the pool at the end of the tunnel, would have been used by the inhabitants as water sources. Troops positioned outside the walls wouldn't have reached any of it, because even the overflow water released from the Pool of Siloam would have fully disappeared into a karstic system located right outside the southern tip of the city walls. In contrast to that, the previous water system did release all the water not used by the city population into the Kidron Valley to the east, where besieging troops could have taken advantage of it.

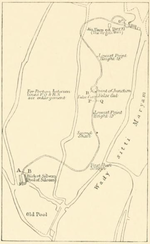

The curving tunnel is 583 yards (533 m; about 1⁄3 mile) long and by using the 12 inch (30 cm) altitude difference between its two ends, which corresponds to a 0.06 percent gradient, the engineers managed to convey the water from the spring to the pool.

According to the Siloam inscription, the tunnel was excavated by two teams, one starting at each end of the tunnel and then meeting in the middle. The inscription is partly unreadable at present, and may originally have conveyed more information than this. It is clear from the tunnel itself that several directional errors were made during its construction. Recent scholarship has discredited the idea that the tunnel may have been formed by substantially widening a pre-existing natural karst. How the Israelite engineers dealt with the difficult feat of making two teams digging from opposite ends meet far underground is still not fully understood, but some suggest that the two teams were directed from above by sound signals generated by hammering on the solid rock through which the tunnelers were digging.