Hokendauqua, Pennsylvania

Census-designated places in Lehigh County, PennsylvaniaCensus-designated places in PennsylvaniaPages with non-numeric formatnum argumentsUse mdy dates from July 2023

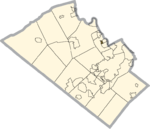

Hokendauqua is an unincorporated community and census-designated place (CDP) in Whitehall Township in Lehigh County, Pennsylvania, United States. The population of Hokendauqua was 3,340 as of the 2020 census. Hokendauqua is a suburb of Allentown, Pennsylvania in the Lehigh Valley metropolitan area, which had a population of 861,899 and was the 68th-most populous metropolitan area in the U.S. as of the 2020 census. The word Hokendauqua is shortened to "Hokey" (pronounced "hockey") in local dialect. It uses the Whitehall ZIP code of 18052.

Excerpt from the Wikipedia article Hokendauqua, Pennsylvania (License: CC BY-SA 3.0, Authors, Images).Hokendauqua, Pennsylvania

Vine Street, Whitehall

Geographical coordinates (GPS) Address Nearby Places Show on map

Geographical coordinates (GPS)

| Latitude | Longitude |

|---|---|

| N 40.659444444444 ° | E -75.490833333333 ° |

Address

Vine Street

Vine Street

18052 Whitehall

Pennsylvania, United States

Open on Google Maps